A flea in one’s…foot?

I sometimes wonder what strange combination of circumstances determines what a young animal enthusiast will become passionate about. With somewhere between five and ten million species to choose from why are some turned on by basking sharks and others by butterflies? How does someone choose between lumbricid worms and lemurs or sea squirts and songbirds?

Seeing these lion cubs in Botswana was wonderful, but ultimately, just another mammal.

If you were able to pick one animal – anything in the world – to see in its natural habitat, what would it be? Lions on the Serengeti? How about swimming with manta rays? What if you could make a top ten list of creatures to see in the wild? It’s true that most people would turn immediately to what’s known as the charismatic megafauna: things large and furry or feathered. There is indeed no denying the majesty of an African elephant or the sleek beauty of a Bengal tiger, but these larger beasts make up only a miniscule fraction of the different ways to be an animal. Making a more inclusive zoological bucket list opens up, quite literally, a world of possibilities. I recommend it wholeheartedly.

The rewards to be gained from pursuing animal obscurities are palpable. It’s truly wonderful to see a bird of paradise dancing in a rainforest canopy but, for me, far more fascinating to watch a parasitic fly fighting to lay its eggs in the head of an angry ant on the forest floor below. Parasites have some of the most convoluted and intriguing life cycles of any creatures, but rarely feature on anyone’s wildlife wish list. Understandably it makes sense to keep most parasites at a safe distance wherever possible, but sometimes you’re forced to experience one in its natural habitat. Sometimes that habitat is you. One of my own most memorable wildlife experiences was when my body was, for a brief period, home to a very strange creature, an animal known as the chigoe flea.

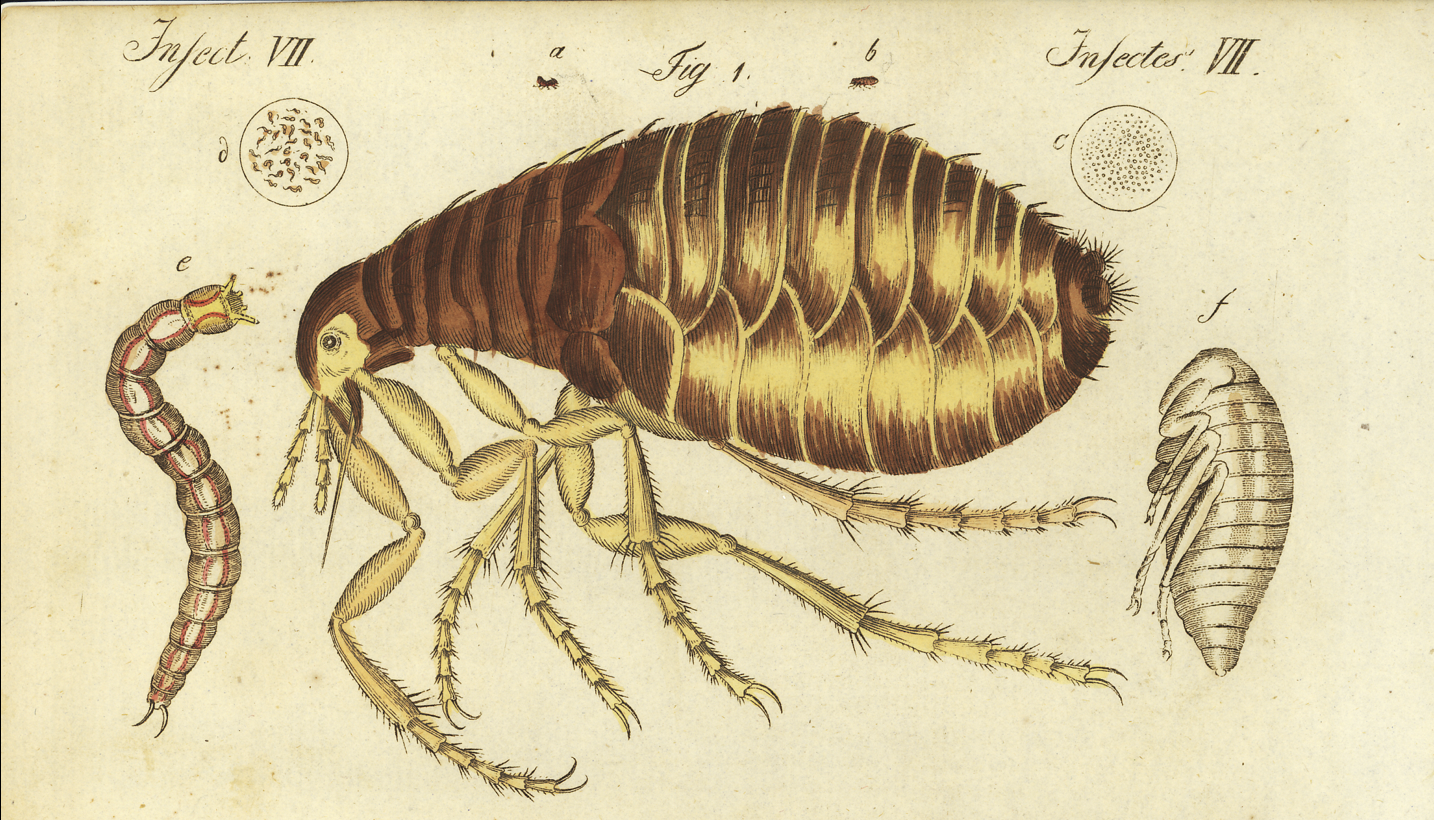

Fleas have a curious evolutionary backstory. They are descended from an ancestor that had wings, probably a predator that hunted other insects. After a series of drastic changes over millions of years, fleas have ended up inextricably tied to their mammal and bird hosts. Their physical and behavioural blueprints are based upon the chinks in the armour of these animals, upon which they rely for a meal of blood. The tough armour and flattened shape of a flea allows it to travel through a forest of fur and resist being deposed by a scratching paw, and their catapult-like jumping mechanism allows them to reach a passing host at lightning speed. Fleas infest a relatively large range of hosts, most birds and mammals being victims, but almost all fleas are remarkably similar in their form and habits.

Fleas have long been notorious for their ability to track down a host.

An adult flea lives on the host or in its nesting material, feeding occasionally by inserting sharp mouthparts into the tissue to tap into a supply of nutritious blood. After mating, eggs are laid and drop off onto the ground or into the host’s nest where they hatch into worm-like larvae. These larvae feed on a range of organic detritus including dried drops of blood excreted by the adult during feeding. After shedding their soft exoskeleton several times the larvae develop into pupae and wait for a sign that a host is nearby – movement, body heat or carbon dioxide – before emerging as adults. I have a fondness for fleas and have some specimens in my cabinet of curiosities, including several of the world’s largest, Hystricopsylla schefferi, a species which should come with a prize if you can pronounce its name on your first try. These relative monsters, which can grow around a centimetre long, are found only on the mountain beaver, Aplodontia rufa, a little-known North American rodent that can only hope to become as famous as its gargantuan parasite. Having secured specimens of the world’s largest flea, it seemed appropriate that I should also be looking for the world’s smallest. As it turns out I didn’t need to: it found me.

It was in sub-tropical Madagascar that the chigoe flea tracked me down. Known more properly as Tunga penetrans, this flea does things differently to every other. The larvae are quite normal and the adults resemble other fleas, albeit far smaller than most (around 1mm long at their largest). It’s when the females find a host – often a human – that their lives take a drastic turn. Rather than just feeding on their host they become internal parasites. Their tiny size allows them to burrow into flesh, usually on the soles of the feet. Here they implant themselves and will remain there for the rest of their lives. But it gets even stranger than that. Once implanted the females swell to several hundred times their original size as they fill with eggs. The largest reach the size of a plump garden pea. As each egg is laid it drops from the flea’s protruding abdomen and falls into the sand, lacing it with larvae ready to develop into the next generation.

The extraction in progress. Photo by Lucia Chmurova.

My own lodger came as a surprise. The regular evening foot check had concluded with nothing to report, but for a tiny dark dot that looked like a splinter or speck of dirt. A few days and several thorough washes later and the dark spot was still there, larger and more ominous. It was at this point that I consulted our local guide who confirmed with grin that it was indeed a chigoe flea. I will admit now that my main response was a giddy excitement as I looked forward to seeing this unique creature close up. I had my flea, but how to remove it? I am all for the preservation of species, but when it comes to individuals living in the sole of my foot I think it’s fair to call it a day quite swiftly. Hoby (pronounced Hooby), the wildlife expert who had identified my steadily expanding interloper, volunteered to set her free. Armed with a needle and a steady hand, he laid me face up on a long bench with my foot in his lap and started to excavate. With the determination and precision of a topsy-turvy dentist he prodded and poked. Other than a slight stabbing pain when my foot received, well, a slight stabbing, as the flea was being prized out, it was an unremarkable procedure. After around five minutes of enlarging the opening in my foot to a couple of millimetres across, the flea was squeezed out whole; a strange white blob, round and surprisingly rigid. Looking more closely I could make out what looked like the front and rear ends of a normal flea, sandwiching the huge corpulent abdomen. As it lay on the bench next to me I noticed a tiny white egg had popped out from the distended body, a last-ditch attempt to produce another generation of burrowing bloodsuckers.

My very own, personal specimen of Tunga penetrans

I don’t expect everyone to be as excited as me by the prospect of ticking another animal obscurity off the bucket list. Parasites in particular are not everyone’s cup of tea. But I would argue that seeing animals like the chigoe flea – the creatures that go out of their way to do something genuinely different – are the most rewarding wildlife experiences there are. There are some who take the very existence of chigoe fleas, leeches and bot flies as a good reason never to leave the house again. I can confirm however, that the thought of being home to a parasite like this is almost always worse than the experience itself. And an infestation is worth its weight in gold when you factor in how many times you’ll tell the story to queasy, wide-eyed listeners, awe-struck at your adventurousness. The worst part of my encounter with the chigoe flea was having the tune to ‘I’ve got you under my skin’ stuck in my head for days afterwards, and a small empty hole in my foot that had sealed itself up a week later. Now the small scar has all but gone and I have another specimen for my cabinet of curiosities. It sits on a shelf in between a small jar of leeches that I picked off my ankles in Borneo and a vial of parasitic mites that found me in Papua New Guinea. And I won’t be telling you where I discovered them.